html`<a style="padding: 0; margin-top: -5px;" href="${await FileAttachment("./images/Reason_Foundation__Montana_HB226_(2023)_Bill_Review_(as of 01192023).pdf").url()}" download>

<button>

<i class="bi bi-filetype-pdf"></i> Download this Analysis

</button>

</a>`HB226 - Montana Reform Improves Pension Funding and Retirement Savings for Public Employees

Steven Gassenberger

Nearly two years after House Joint Resolution 8 set legislators on the interim task of finding a long-term solution to funding state pension benefits—an approach that sought to recognize “the concerns of all Stakeholders, including the citizens of Montana”—lawmakers have been presented with a reform that would greatly improve the funding and security of the state’s retirement plan. House Bill 226 (HB226) of 2023, introduced by Billings Representative Terry Moore, guarantees active and retired members of Montana’s Public Employees Retirement System (PERS) will have every penny of their earned benefits funded while also supporting the retirement savings goals of the majority of public employees.

Current Structure and & Challenges of Montana’s Public Employee Retirement System

As currently structured, PERS offers new employees a choice between a traditional Defined Benefit Retirement Plan (PERS-DB) and a Defined Contribution Retirement Plan (PERS-DC), with the defined benefit (or pension) plan serving as the default. New employees may choose to join the PERS-DC plan at any time during their initial 12 months of employment. If no selection is made, the employee is automatically registered as a member of the PERS-DB plan. The two main differences between the PERS-DB and PERS-DC are the guarantee of lifetime benefits and the portability of an individual’s retirement savings:

The PERS-DB offers members who work with a participating public employer for at least five years a predetermined monthly benefit check in retirement in exchange for contributions throughout their tenure in public employment. Over 53,000 active and retired beneficiaries have defaulted or chosen to remain in the PERS-DB.

The PERS-DC offers members a predetermined employer contribution toward a member’s personal retirement account, in which a member becomes vested after 5 years. Members can take their benefits with them upon leaving employment to do with it what they determine is best for them and their families. Currently, about 5,000 members have elected the PERS-DC benefit option.

Each of the state’s two retirement benefit options for public employees come with their own advantages and both offer valuable retirement benefits to public workers. However, the funding risks associated with the PERS-DB has been a perennial challenge for Montana appropriators.

In 2001, the PERS-DB did not have any unfunded obligations. Poor investment outcomes below previous expectations have subsequently left today’s PERS-DB fund with the highest unfunded liabilities in the plan’s history despite a historic 29% market return in 2021.

Source: Pension Integrity Project analysis of PERS actuarial reports and ACFRS.

According to the latest reports, the PERS-DB fund is currently 75% funded, with just over $2 billion in unfunded pension liabilities. (See Figure 1) Investment conditions are expected to worsen, according to PERS consultants and market watchers, in large part due to volatility expected throughout the global investment markets from which nearly 60% of the fund’s growth is derived.

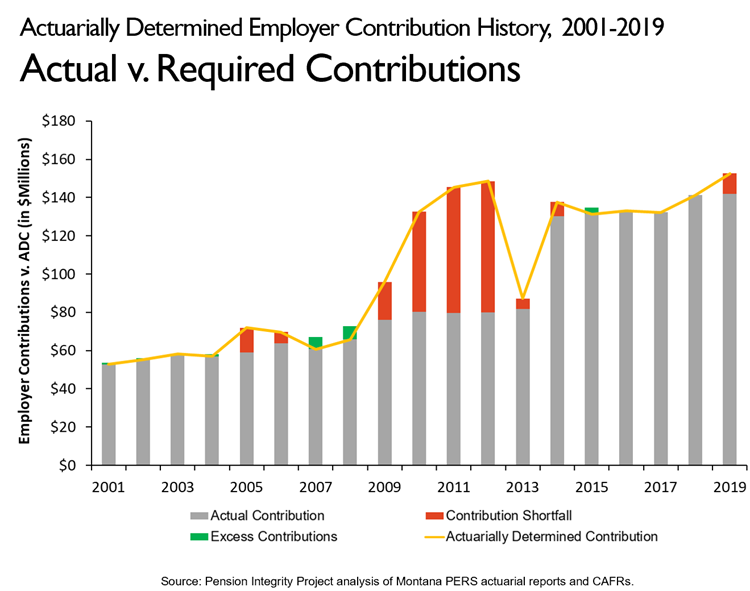

Undergirding the PERS-DB fund are contributions from public employers and participating employee members. As of the 2022 PERS valuation, members contributed 7.9% of their salary to the PERS fund while the state and their public employers contribute 11.58%. While the member rate has remained relatively constant over the last few decades, the employer rate has risen substantially and is slated to continue that rise over the next few years. Despite this rising trend, employer contributions to PERS have frequently fallen short of the amount plan actuaries determined would be needed to reach 100% funding in 30 years.

The main culprit for this misalignment between the funding needs of the PERS-DB fund and the actual contributions being made to the plan is the use of statutory contribution rates. (Figure 2) This means the PERS-DB employer contribution rate does not change unless the legislature acts to adjust the rate fixed in state law. Increasing the employer contribution rate in this manner is cumbersome and often too unresponsive, particularly in challenging economic times.

Figure 2

PERS administrators have readily acknowledged these challenges associated with the way employers contribute to the fund. According to a 2020 Legislative Fiscal Division report “…current funding policies leave the systems heavily reliant on investment earnings and unable to adjust contributions to maintain an actuarially sound basis in times of significant financial declines.”

When PERS actuaries use the system’s latest assumptions and experience data to calculate the system’s value, they also determine annually how long it will take for all earned and expected benefits to be fully funded, commonly known as a system’s amortization period. (Figure 3)

PERS Amoritization Period History

- 2022: 32-year amortization period

- 2020: 35-year amortization period

- 2017: 30-year amortization period

- 2014: 29-year amortization period

- 2013: 14.5-year amortization period

The Society of Actuaries recommends amortizing unfunded pension liabilities over a 15 to 20-year period; however, Montana PERS funding is based on a much longer 30-year period. The effect of a longer amortization period is a decrease in the immediate short-term costs but at the expense of much higher costs over the long term, and significant risk of prolonged underfunding due to investment returns below expectations. Long amortization periods, when combined with statutory contribution rates, are indicators that plan amortization payments are likely to be insufficient to pay down the unfunded liability and the additional subsequent interest debt it accrues.

HB226 Guarantees Benefits Will Be Fully Funded

Since the passage of House Bill 454 (2013), the state has consistently increased pension contributions every year to make up for unfunded pension obligations, yet the system’s funded ratio today still stands at 75%, barely higher than the 74% funded status PERS had at the time of HB454’s passage. The challenge lies with the system’s currently outdated funding policy that relies on contribution rates set in statute.

While setting contributions in statute make annual payments predictable for government budgets, the true costs of funding taxpayer-guaranteed pensions vary over time in response to changing market conditions.

Instead of systematically tracking inherent changes in costs, Montana historically increased its employer rate in response to growth in unfunded liabilities—usually after a long review period and a formal request from pension administrators. (Figure 3)

How Montana’s Current Variable-Statutory Employer Contribution Rate Adjusts

If a pension system actuary calculates an amortization period:

- Greater than 30 years: The actuary will recommend a contribution rate increase that can expect to fully amortize the UAAL over a closed 30-year period.

- Less than 30 years, but greater than 0 and is projected to continue to decline over the remainder of the closed period: The actuary will not recommend a change in the statutory contribution rates.

- Less than 30 years, but has increased over prior valuations and is projected to continue to grow: The actuary will recommend a contribution rate increase that is expected to reverse the trend and re-establish a closed amortization period equal to that of the last valuation.

This process passively allows unfunded liabilities to compound from one fiscal year to the next since the current funding policy is not immediately responsive to market conditions and pension system performance. Worse, in combination with poor funding policy, Montana PERS also uses an ineffective approach to amortizing unfunded liabilities that simply refinances unfunded liabilities each year, instead of adopting a policy to pay off any new unfunded liabilities by a fixed date.

The technical term for annually refinancing your unfunded pension liabilities instead of putting them on a closed end-date path is “open amortization.” Since open amortization resets annually, it is similar to refinancing a home mortgage every year. The result of this policy in Montana has seen marginal progress on eliminating unfunded obligations over the last decade.

Actuarially determined funding policy, commonly referred to ADEC funding, as HB226 (2023) would adopt, commits the state and participating employers to fully funding benefits with an explicit target year to pay down any legacy or newly accrued debt. Moving from the current statutory funding method to a method where plan actuaries determine employer contribution rates presents the best opportunity for policymakers to help improve the long-term cost and resiliency of the PERS-DB plan. (Figure 4)

Source: Pension Integrity Project actuarial forecast of PERS plan. The annual rate of return is assumed to be a constant 6%. Using Actuarially Determined Contribution (ADEC) rates, unfunded liabilities are amortized over 30 years using a layered-base, level dollar method of amortization. Years are plan’s fiscal years.

During an August 2020 hearing of the Legislative Finance Committee, PERS actuaries pointed out that “states are getting away from the old statutory funding method” and that “an actuary’s dream funding policy” is a system that adjusts “to keep up with how the plan is doing.”

HB226 (2023) Aligns PERS to better Serve the Majority of Public Employees

As of the 2022 PERS valuation, a new public employee that enters the PERS-DB will see at least 7.9% of their paycheck contributed to the pension fund until they leave public employment. For those who leave within five years of being hired, the PERS-DB acts more like a temporary savings account, giving the employee back only what they themselves put into the system, plus interest, while forfeiting any employer contributions made toward their pension benefit.

According to our estimates using PERS assumptions, 70% of all new hires starting in their early twenties will find other positions outside of Montana public service within five years. Only 9% of employees hired in their early-20’s stay employed for the 30 years required to earn an unreduced PERS-DB retirement. The current system serves only a fraction of public employees at an ever-rising cost.

HB226 (2023) recognizes this trend and swaps the default benefit offered to new hires from the PERS-DB plan to the PERS-DC plan. This will allow for more portability and greater retirement security for the vast majority of employees, not just a small group of long-haulers. The measure maintains the current PERS-DB benefit as an option for new hires who intend to serve out their career in public employment. . Current PERS-DB active members, retirees and their beneficiaries are not affected by the new default policy.

PERS-DB Before and After HB226 (2023)

The following figures compare the PERS system (DB and DC benefits combined) in its current state to the PERS system under a scenario where HB226 (2023) is adopted.

Assuming all investment and demographic assumptions prove accurate over the next 30 years, Figure 5 and Figure 6 project the annual costs and funding of the PERS-DB in its current state to PERS-DB after the adoption of HB226.

Under the scenario in which actual returns match plan assumptions each year, HB226 (2023) would increase employer contributions over the next decade but would also allow for a lower contribution in later years. Additionally, the reform would slightly accelerate the PERS-DB’s path to full funding. Actual returns will not match plan assumptions year to year, however, and there is a good chance that long-term results will continue to return below the assumptions used. The proposed reform’s true effect is most evident when investment projections deviate from the plan’s return assumptions.

Source: Pension Integrity Project actuarial forecast of PERS plan. The annual rate of return is assumed to be a constant 7.3%. Under HB226, the legacy unfunded liability is amortized over 30 years with a level dollar method; while new unfunded liabilities are amortized over 10 years under a layered-base, level dollar method. Years are plan’s fiscal years.

Source: Pension Integrity Project actuarial forecast of PERS plan. The annual rate of return is assumed to be a constant 7.3%. Under HB226, the legacy unfunded liability is amortized over 30 years with a level dollar method; while new unfunded liabilities are amortized over 10 years under a layered-base, level dollar method. Years are plan’s fiscal years.

Figures 7 and 8 introduce market volatility into the actuarial equation. The results show how, although the current funding policy maintains a lower contribution level, millions of earned retirement benefits will go underfunded and continue to drive up cost long-term.

Source: Pension Integrity Project actuarial forecast of PERS plan. The annual rate of return is assumed to be a constant 7.3%, except for 0% in year 2025. Under HB226, the legacy unfunded liability is amortized over 30 years with a level dollar method; while new unfunded liabilities are amortized over 10 years under a layered-base, level dollar method. Years are plan’s fiscal years.

Source: Pension Integrity Project actuarial forecast of PERS plan. The annual rate of return is assumed to be a constant 7.3%, except for 0% in year 2025. Under HB226, the legacy unfunded liability is amortized over 30 years with a level dollar method; while new unfunded liabilities are amortized over 10 years under a layered-base, level dollar method. Years are plan’s fiscal years.

Figures 9 and 10 use the Pension Integrity Project’s modeling to show how the PERS pension plan will respond to a future recession like the one following the Dot.com boom of the late 1990s. If PERS-DB experiences similar asset losses to those it did in the past recession, the system would continue to accrue unfunded liabilities and lawmakers and employers will remain responsible for expensive amortization payments under the status quo funding policy.

Source: Pension Integrity Project actuarial forecast of PERS plan. The annual rates of return for period 2025-2029 are assumed to match the returns in period 2001-2005. Under HB226, the legacy unfunded liability is amortized over 30 years with a level dollar method; while new unfunded liabilities are amortized over 10 years under a layered-base, level dollar method. Years are plan’s fiscal years.

Source: Pension Integrity Project actuarial forecast of PERS plan. The annual rate of return is assumed to be a constant 7.3%. Under HB226, the legacy unfunded liability is amortized over 30 years with a level dollar method; while new unfunded liabilities are amortized over 10 years under a layered-base, level dollar method. Years are plan’s fiscal years.

Switching Montana’s pension funding policy from reactive to proactive by committing to contributions at a rate determined by plan actuaries leads to long-term savings, and making the DC plan the default choice for new workers would help reduce the chances of accruing future unfunded liabilities (see Table 1). Depending on actual market results, HB226 (2023) could save the state as much as $54 million over the next 30 years, despite offering a significantly higher valued DC plan for most employees.

Table 1

This actuarial analysis shows that Montana’s current approach to funding the PERS-DB is the most unsustainable path forward. The changes proposed in HB226 (2023) would generate significant risk reduction. This effect is even more prominent if the system experiences economic volatility similar to the last two decades.

Fiscal Considerations

During previous sessions, many budget-aware stakeholders and legislators expressed concerns over the potential contribution increases associated with the state adopting policies like those in HB226 (2023). Table 2 compares the status quo with the proposed funding policy included in HB226 (2023) from an employer cost perspective. In exchange for prudent, navigable increases in the short-term, employers could not only expect a drop in required contribution about 12 years out but a complete elimination of all unfunded actuarially accrued liabilities (UAL), which are earned retirement benefits for which sufficient funds must be set aside.

Table 2

The near-term rise in employer contributions required under HB22 (2023) can be mitigated to some degree with technical adjustments, but not avoided entirely regardless of if the solutions found in HB226 (2023) are adopted or not. The over $2.2 billion in earned retirement benefits currently unfunded will need to be paid somehow, and the bill will inevitably come due. HB226 (2023) accepts this reality and commits to honoring the state’s obligations in the interest of future Montanans.

Conclusion

Shifting to a shorter, layered amortization schedule would lead to the faster payment of unfunded pension liabilities. Although shortening the amortization schedule can lead to a temporary increase in the employer contributions immediately, it saves the state and taxpayers more long-term, while providing a more stable pension plan for public employees.

With HB226 (2023), Montana lawmakers now have a direct path to a secure and sustainable retirement system that better supports all of its members. Adopting a sustainable funding policy and aligning defaults with the habits of the majority of public employees is a proven way to improve the long-term sustainability of PERS and attract quality public servants going forward.